Port Gibson, Mississippi

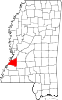

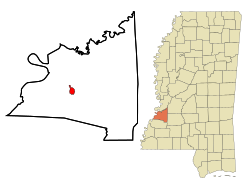

Port Gibson, Mississippi | |

|---|---|

Claiborne County Courthouse and Confederate monument in Port Gibson | |

| Motto: "Too beautiful to burn" | |

Location of Port Gibson, Mississippi | |

| Coordinates: 31°57′22″N 90°58′59″W / 31.95611°N 90.98306°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Claiborne |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Willie A. White |

| Area | |

• Total | 1.75 sq mi (4.55 km2) |

| • Land | 1.75 sq mi (4.55 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 118 ft (36 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 1,269 |

| • Density | 723.08/sq mi (279.18/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 39150 |

| Area code | 601 |

| FIPS code | 28-59560 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0676254 |

| Website | portgibsonms |

Port Gibson is a city and the county seat of Claiborne County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 1,567 at the 2010 census.[2] [3] It is bordered on the west by the Mississippi River.

The first European settlers in Port Gibson were French colonists in 1729; it was part of their La Louisiane. After the United States acquired the territory from France in 1803 in the Louisiana Purchase, the town was chartered that same year. To develop cotton plantations in the area after Indian Removal of the 1830s, planters who moved to the state brought with them or imported thousands of enslaved African Americans from the Upper South, disrupting many families. Well before the Civil War, the majority of the county's population were enslaved.

Several notable people are natives of Port Gibson. The town saw action during the American Civil War. Port Gibson has several historical sites listed on the National Register of Historic Places (National Register of Historic Places listings in Claiborne County, Mississippi).

In the twentieth century, Port Gibson was home to The Rabbit's Foot Company. It had a substantial role in the development of blues in Mississippi, operating taverns and juke joints now included on the Mississippi Blues Trail.

In the second half of the twentieth century many jobs in agriculture were lost because of industrialization, which, combined with a lack of other jobs, has led to a substantial loss of population and to poverty in the city and the surrounding county. Port Gibson's population peaked in 1950. The last major employer, the Port Gibson Oil Works, a cottonseed mill, closed in 2002.

History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2022) |

Port Gibson is the third-oldest European-American settlement in Mississippi. Its development began in 1729 by French colonists and was then within French-claimed territory known as La Louisiane. The British acquired this area after the French ceded their colonies east of the Mississippi River in 1763,[4] following their defeat in the Seven Years' War.

Following the U.S. acquisition of former French territory through the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, more Americans entered the area. Port Gibson was chartered as a town that year on March 12, 1803. The federal government carried out Indian Removal in the 1830s, pushing the Five Civilized Tribes, including the Choctaw and Chickasaw peoples, west of the Mississippi River to Indian Territory. It took over their lands in the Southeast for sale and development by European Americans.

Planters developed cotton plantations in the fertile river lowlands of the Mississippi Delta and other riverfront areas, dependent on the labor of enslaved Africans, initially brought from the Upper South. The African Americans comprised a majority in the county before the Civil War, and this continued.

With international demand high for cotton, such planters prospered. As the planter population increased, they founded the Port Gibson Female College in 1843 to educate their daughters. The college later closed and one of its buildings now serves as the city hall.[5] Similarly, they founded Chamberlain-Hunt Academy in 1879, a military preparatory boarding school which became co-ed in 1971. CHA was the legacy of Oakland College founded in 1830 in nearby Lorman. Oakland was closed during the Civil War and the Oakland campus was sold to the State of Mississippi to create Alcorn A&M College, the first land-grant college for African Americans. Chamberlain-Hunt closed its doors in 2014. In 1990, the first African American students graduated from Chamberlain-Hunt.

Port Gibson was the site of several clashes during the American Civil War and figured in Union General Ulysses S. Grant's Vicksburg Campaign. He was attempting to gain control over the Mississippi River. The Battle of Port Gibson occurred on May 1, 1863, and resulted in the deaths of more than 200 Union and Confederate soldiers. The Confederate defeat resulted in their losing the ability to hold Mississippi and defend against an amphibious attack.

Later nineteenth century to present

[edit]Reportedly, many of the historic buildings in the town survived the Civil War because Grant proclaimed the city to be "too beautiful to burn". These words appear on the sign marking the city limits.[6]

Despite postwar economic upheaval, the city continued as a center of trade and economy associated with cotton. In 1882, the Port Gibson Oil Works started operating, established as one of the first cottonseed oil plants in the United States.[7] This historic industrial building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979.[8] The mill finally closed in 2002.[4]

Gemiluth Chessed synagogue, built in 1892, had an active congregation when the town was thriving as the county seat and a trading center. It had attracted nineteenth-century Jewish immigrants from the German states and Alsace-Lorraine. After starting as peddlers, the later generations of men became cotton brokers and merchants. This is the oldest synagogue and the only Moorish Revival building in the state.[9] It is topped by a Russian-style dome. As the economy changed, the Jewish population gradually moved to larger cities and areas offering more opportunity, and none remain in Port Gibson.

The Rabbit's Foot Company was established in 1900 by Pat Chappelle, an African-American theatre owner in Tampa, Florida. This was the leading traveling vaudeville show in the southern states, with an all-black cast of singers, musicians, comedians, and entertainers.[10]

After Chappelle's death in 1911, the company was taken over by Fred Swift Wolcott, a white planter. After 1918, he based the touring company at his plantation near Port Gibson, with offices in town. He continued to manage it until 1950, when he sold it. The Rabbit's Foot Company remained popular, but as some white performers joined and used blackface, it was no longer considered "authentic".[10]

In 2002 the New York Times characterized Port Gibson as 80 percent black and poor, with 20 percent of families living on incomes of less than $10,000 a year, according to the 2000 Census. It also had an "entrenched population of whites, many of whom are related and have some historical connection to cotton".[11]

Legacy

[edit]A Mississippi Blues Trail marker was placed in Port Gibson to commemorate the contribution the Rabbit's Foot Company made to the development of the blues in Mississippi, in its decades of operation after the founder's death.[12]

In 2006, an exhibition, The Blues in Claiborne County: From Rabbit Foot Minstrels to Blues and Cruise, was shown in Port Gibson, exploring the history of the show, with artifacts and memorabilia.[13]

Other National Register of Historic Places buildings and sites

[edit]- Van Dorn House, completed c. 1830, built by Peter Aaron Van Dorn, a lawyer, planter, and judge

- McGregor, house designed in Greek Revival style by Van Dorn (above) for one of his daughters, completed 1835

- Windsor Ruins, 23 columns of a plantation house that burned c. 1890, located about ten miles southwest of the city that have been featured in two motion pictures

- Wintergreen Cemetery, historic cemetery with burials of notable residents

Geography

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 1.8 square miles (4.7 km2), all land.

Climate

[edit]| Climate data for Port Gibson, Mississippi (1991–2020, extremes 1893–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 88 (31) |

87 (31) |

94 (34) |

94 (34) |

99 (37) |

104 (40) |

104 (40) |

107 (42) |

105 (41) |

97 (36) |

89 (32) |

84 (29) |

107 (42) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 59.5 (15.3) |

63.7 (17.6) |

71.0 (21.7) |

77.9 (25.5) |

84.9 (29.4) |

90.5 (32.5) |

92.9 (33.8) |

93.4 (34.1) |

89.1 (31.7) |

80.1 (26.7) |

69.1 (20.6) |

61.5 (16.4) |

77.8 (25.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 47.6 (8.7) |

50.9 (10.5) |

58.4 (14.7) |

65.2 (18.4) |

73.2 (22.9) |

79.8 (26.6) |

82.3 (27.9) |

82.2 (27.9) |

77.2 (25.1) |

66.6 (19.2) |

55.9 (13.3) |

49.8 (9.9) |

65.8 (18.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 35.7 (2.1) |

38.1 (3.4) |

45.9 (7.7) |

52.5 (11.4) |

61.5 (16.4) |

69.1 (20.6) |

71.8 (22.1) |

70.9 (21.6) |

65.3 (18.5) |

53.1 (11.7) |

42.7 (5.9) |

38.1 (3.4) |

53.7 (12.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −5 (−21) |

−1 (−18) |

15 (−9) |

26 (−3) |

34 (1) |

45 (7) |

51 (11) |

51 (11) |

35 (2) |

23 (−5) |

15 (−9) |

4 (−16) |

−5 (−21) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 6.10 (155) |

5.06 (129) |

6.01 (153) |

5.45 (138) |

4.47 (114) |

4.05 (103) |

3.94 (100) |

3.56 (90) |

3.75 (95) |

4.11 (104) |

4.44 (113) |

5.32 (135) |

56.26 (1,429) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.2 (0.51) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.5 (1.3) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.9 | 8.4 | 8.8 | 7.6 | 7.9 | 8.9 | 9.4 | 8.3 | 6.8 | 5.8 | 7.4 | 8.8 | 98.0 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| Source: NOAA[14][15] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1890 | 1,524 | — | |

| 1900 | 2,113 | 38.6% | |

| 1910 | 2,252 | 6.6% | |

| 1920 | 1,691 | −24.9% | |

| 1930 | 1,861 | 10.1% | |

| 1940 | 2,748 | 47.7% | |

| 1950 | 2,920 | 6.3% | |

| 1960 | 2,861 | −2.0% | |

| 1970 | 2,589 | −9.5% | |

| 1980 | 2,371 | −8.4% | |

| 1990 | 1,810 | −23.7% | |

| 2000 | 1,840 | 1.7% | |

| 2010 | 1,567 | −14.8% | |

| 2020 | 1,269 | −19.0% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[16] | |||

| Race | Num. | Perc. |

|---|---|---|

| White | 122 | 9.61% |

| Black or African American | 1,122 | 88.42% |

| Other/Mixed | 20 | 1.58% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 5 | 0.39% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 1,269 people, 554 households, and 290 families residing in the city.

Education

[edit]Port Gibson is served by the Claiborne County School District.[18] Port Gibson High School is the comprehensive high school of the district.

The Chamberlain-Hunt Academy, a private military boarding school, opened in Port Gibson in 1879. It was promoted as a Christian school in the late twentieth century. Nonetheless, it suffered declining enrollment and closed in 2014.[19]

Notable people

[edit]- Samuel Reading Bertron, banker

- Cleo W. Blackburn, educator[20]

- Pete Brown, golfer, first African American to win on the PGA Tour

- Jay Disharoon, lawyer and Mississippi legislator

- Henry Hughes, lawyer, sociologist, state senator, and Confederate colonel[21]

- Yolanda Moore, former professional basketball player and girls basketball coach[22]

- Betty Berry Morgan, writer

- Jacob S. Raisin, rabbi

- Irwin Russell, poet

- Bob Shannon, high school football coach, known for his work in East St. Louis, Illinois[23]

- V. C. Shannon, born in Port Gibson in 1910, one-term member of the Louisiana House of Representatives from Shreveport, serving from 1972 to 1974

- J. D. Short, Delta blues guitarist, singer, and harmonicist[24]

- James G. Spencer, U.S. Representative from 1895 to 1897[25]

- Clement Sulivane, Confederate officer, politician, and member of the Maryland Senate from 1878 to 1880[26]

- Earl Van Dorn, Confederate Civil War general

- Peter Aaron Van Dorn, lawyer, judge, plantation owner, and one of the founders of Jackson, Mississippi[27]

- F. S. Wolcott, minstrel show proprietor

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (DP-1): Port Gibson city, Mississippi". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ^ a b Kilborn, Peter T. (18 October 2002). "A Vestige of King Cotton Fades Out in Mississippi". New York Times. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ Patti Carr Black; Marion Barnwell (2002). Touring Literary Mississippi. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 179. ISBN 978-1-57806-368-0. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ^ Hendrickson, Paul (2003). Sons of Mississippi. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-375-40461-9.

- ^ Gold, Jack A. (January 1979), Historic Sites Survey: Port Gibson (cottonseed crushing) Oil Works Mill Building (PDF), retrieved August 5, 2018.

- ^ National Park Service, NPGallery: Port Gibson Oil Works Mill Building, retrieved August 5, 2018.

- ^ Peter Applebome (September 29, 1991). "Small-Town South Clings to Jewish History". New York Times. Retrieved September 1, 2011.

- ^ a b Lynn Abbott, Doug Seroff, Ragged But Right: Black Traveling Shows, Coon Songs, and the Dark Pathway to Blues and Jazz, University Press of Mississippi, 2009, pp.248-268

- ^ PETER T. KILBORN, "A Vestige of King Cotton Fades Out in Mississippi", New York Times, October 18, 2002.

- ^ "Mississippi Blues Commission - Blues Trail". www.msbluestrail.org. Retrieved 2008-05-28.

- ^ "Rabbit Foot Minstrel Exhibit in Port Gibson Until September 30, 2006". h-southern-music. Retrieved 10 July 2014

- ^ "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 16, 2023.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991-2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 16, 2023.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved 2021-12-07.

- ^ "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Claiborne County, MS" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-07-31. Retrieved 2022-07-31. - Text list

- ^ "Chamberlain-Hunt Academy to Close". WAPT Jackson. July 30, 2014.

- ^ David J. Bodenhamer; Robert G. Barrows (22 November 1994). The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Indiana University Press. p. 323. ISBN 0-253-11249-4.

- ^ Drew Gilpin Faust (1 September 1981). The Ideology of Slavery: Proslavery Thought in the Antebellum South, 1830–1860. LSU Press. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-8071-0892-5.

- ^ "Yolanda Moore Named Girls Basketball Coach At Heritage Academy". Ole Miss Sports. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ Kevin Horrigan (1993). The Right Kind of Heroes: Coach Bob Shannon and the East St. Louis Flyers. HarperPerennial. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-06-097578-4.

- ^ PETER KRAMPERT (23 March 2016). The Encyclopedia of the Harmonica. Mel Bay Publications. p. 159. ISBN 978-1-61911-577-4.

- ^ Nancy Capace (1 January 2001). Encyclopedia of Mississippi. Somerset Publishers, Inc. p. 405. ISBN 978-0-403-09603-9.

- ^ Robert E. L. Krick (4 December 2003). Staff Officers in Gray: A Biographical Register of the Staff Officers in the Army of Northern Virginia. Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 278. ISBN 978-0-8078-6307-7.

- ^ Linda Gupton (5 June 2013). Seasons in the South: The Lives Involved in the Death of General Van Dorn. Author House. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-4817-5365-4.